Ancient Roman Animals: the history of animals in Italy.

"The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated" (Mahatma Gandhi).

Ask anyone what they know about ancient Roman animals and their thoughts will tend to go to lions, Christians and the ancient Roman Colosseum.

But evidence from various sources suggests there is more to the Romans and their animals than that.

Ancient Roman architecture and art, mosaics, tombstones, and poets and authors of the time all show us different faces - and some interesting double standards - of an ancient Empire and the treatment of its animals.

This page is all about the importance of animals in the Roman Empire, and how some of those behaviours and traditions have found their way into Italian culture today.

It's a very lengthy article, so to help you get to where you want, here are some handy links.

Click whichever section you're interested in - or read the whole way through!

Ancient Roman animals: beasts of burden or pampered pets?

The treatment of animals generally in the Empire was a direct reflection of ancient Roman culture and traditions. The Romans were especially fascinated with wild animals. They liked looking at them, marvelling at their strangeness, watching them perform tricks - and watching them being hunted and killed.

Wolves, bears, wild boar, deer and goats were native to Rome and other animals were introduced following conquests abroad. Elephants, leopards, lions, ostriches and parrots were imported in the 1st Century B.C. followed by the hippopotamus, rhinoceros, camel and giraffe.

There were no zoos in ancient Rome but looking at our strange facts about the Roman Colosseum will tell you that the Colosseum itself was used as something like a cross between a zoo and a circus.

All these species were used for shows in the arena. Some were also kept by the wealthy for their own entertainment. We know from writings, for example, that monkeys would be dressed as soldiers and ride in small chariots pulled by goats.

|

| Elephant mosaic, Ostia Antica. |

But above all other ancient Roman animals it was the elephant which became a symbol of Roman power and the success of its Emperors.

In 46 B.C., after the defeat of rival Pompey in Greece and successful wars in Asia Minor and Egypt, Caesar held an elaborate triumphant parade in which forty trained elephants marched alongside him up the steps of the Capitol, lighted torches burning in their trunks.

By far the most popular of the ancient Roman animals used for show, outside the arena the elephant was a prized status symbol used to transport wealthy men and women to dinner.

It did of course also have its more serious uses - in the building trade, for example, where it was able to carry, lift and pull huge weights, and as a kind of secret weapon of the ancient Roman military for, as much as anything, frightening enemies who had never seen such large and strange-looking creatures before.

Did ancient Roman animals play any part in family life in ancient Rome?

Horses in Ancient Rome.

|

| Caligula's pampered stallion, Incitatus. |

Just as the more exotic ancient Roman animals were an important part of entertainment in the Empire, horses were as crucial a part of daily life as they are today.

Horses were used extensively by the ancient Roman military, were a part of farming communities as beasts of burden, and were used as animals of entertainment in chariot racing. Respected in all these roles horses were not generally kept as pets or for leisure riding in ancient Rome, with the single exception of Incitatus, the horse of the Emperor Caligula.

The historian Suetonius tells us that Incitatus had his own stable of marble with a manger made of ivory and was attended by eighteen servants who fed him a diet of oats mixed with gold flakes.

The most spoiled of ancient Roman animals, this horse was often to be found dressed in a headcollar of precious stones, wearing a blanket of royal purple and holding his own social gatherings complete with servants. Caligula even promised to appoint Incitatus as consul - a promise he would certainly have carried out had he lived longer.

Some historians believe that Caligula's often foolish treatment of this white stallion may have been an indication of his deteriorating mental state. Others see it as no more than a sign of arrogance in a man who had too much time and money on his hands.

Whichever it may have been, was it much more extreme than the pampering of animals in Italy and other countries today?

|

| Fibula with birds.

Photo courtesy of the vRoma project. |

The role of cats, fish and birds.

Strangely, although the Egyptians had revered cats as god-like creatures and cats in Italy today are a favourite pet, there is no evidence amongst writings about ancient Roman animals that cats were a particularly prized animal.

If kept at all it is likely their value was in helping prevent the spread of rodents.

Fish and birds, on the other hand, were kept for ornamental purposes much as they are today. Exotic species like peacocks, parakeets and parrots were imported from all over the Empire, often housed in cages made from precious metals and regularly adorned ancient Roman jewellery.

Unfortunately, in a contradiction often seen in the treatment of ancient Roman animals, many pets were also considered a delicacy and a pet fish or parrot might eventually end up on the table. Parrots' tongues were a particular delicacy.

There's some reflection of that in Italian culture today, particularly in rural regions where animals have to earn their keep. When we were looking for a house in Marche, we often came across rabbits, pigeons and even peacocks kept as a good source of protein.

Dogs: were they a Roman's best friend?

|

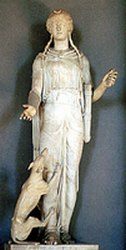

| Diana with hunting dog.

Photo courtesy of the vRoma project. |

The clearest reflection of Italian family traditions today, however, is the role played by dogs in ancient Italy. Humans have had a longer relationship with dogs than with any other domesticated animal, and that relationship began to a large extent in the ancient Roman Empire.

The first recorded book about dogs was written by Marcus Terentius Varro, an officer in the Spanish section of the ancient Roman army, and the Roman poet Grattius in his book about hunting with hounds at around the same time was the first writer to notice likenesses between dogs and their owners.

But they weren't always a person's best friend.

Whilst dogs were sometimes seen as worthy of serving the gods - Diana the huntress, for example, is generally shown with at least one dog by her side - and whilst most people know that other ancient Roman animals were regularly sacrificed to appease the gods, what is not well known is that sometimes in ancient Italy dogs would also be used as religious sacrifices.

Pliny, for example, talks in his writings about suckling pups making excellent sacrifices because of their pure meat.

And although dogs featured amongst other animals in being named in stellar constellations - Canis Major (the Great Dog) which contained the 'dog star' Sirius, for example - dogs did not get the most positive of write-ups in those terms either.

Sirius may have been recognised as the brightest star in the night sky and been viewed by Romans as a second sun, but it was also associated with the unbearable heat of summer days and it was the ancient Romans who first coined the phrase 'dies caniculares', more commonly known in current language as the "dog days of summer".

They also associated Sirius' heat with disease and pestilence, including rabies. Pliny had an interesting 'cure' for rabies: a rabid dog should be fed chicken droppings. If a human catches it, he or she should plunge into an ice cold stream. Simple.

But as well as these negative associations there is overwhelming evidence that generally speaking the Romans held ancient dogs in high regard and used different breeds for a wide variety of purposes, exactly as we do today.

How did ancient Romans treat their dogs?

|

| Rottweiler : the modern Canes Pugnaces. |

Ancient Roman animals appearing in the ancient Roman Colosseum is a well known part of the culture of the time. Lions, leopards, elephants, even ostriches are commonly known to have appeared there as part of the arena's entertainment.

What is not as commonly known is that some breeds of ancient dogs also fought there.

"Canes pugnaces" were the original Roman fighting dogs and perhaps something like the present day Rottweiler. Large, heavy, muscular animals, their fights in the Colosseum were the origins of bull-baiting which became popular in the middle ages, and dog-fighting which goes on today, albeit illegally, in many parts of the world.

Mastiff type dogs were also used in attack formations by the Roman army. There is evidence that each legion had one fighting dog company with dogs dressed for battle in spiked coats, trained to run under the bellies of enemy horses to disembowel them.

|

| English Mastiff - or Pugnaces Britanniae. |

The Roman invasion of Britain introduced another fighting dog, a now extinct breed called the "Pugnaces Britanniae" reported by historian Strabo as introduced to the Empire in about 38 A.D. A large, low, heavy dog with a powerful build, strongly developed head and giant mouth, this breed is recognised as the predecessor of the English Mastiff.

Because of the combination of dignity and courage, calmness with its master and a keenness to protect, this was the ideal fighter and guard dog.

|

| Neapolitan Mastiff : the descendant of the Molossus. |

An ancient breed rediscovered in Italy in the 1940s and now very popular in Italy, the Neapolitan Mastiff is a heavy-boned, massive, awe inspiring dog bred for use as a guard and defender of owner and property.

The predecessor of this breed is one of the most prized of ancient Roman animals - the giant Molossus. "If you are not bent on looks and deceptive graces," writes the poet Grattius, "and when serious work needs doing, when bravery must be shown and the impetuous war-god imposes the greatest hazards, then you cannot help but admire the renowned Molossus."

|

| Cave Canem Mosaic, Pompeii. |

Although also used in the ancient Roman Colosseum, the Molossus was more commonly a guard dog in ancient Italy. There is ample evidence from the remains of Pompeii that dogs were used to guard houses : the remains of a dog chained to a door, an ancient villa's floor mosaic with the words 'Cave Canem' ('beware of the dog') inscribed above it.

But they did not only look after houses. Given that a large part of the Roman Empire was agricultural, the role of dogs in guarding and herding other ancient Roman animals was critical. The Molossus was also used as a herding dog, the difference with the fighting Molossus being that herding dogs were fed a vegetarian diet to prevent them developing a taste for the animals they were supposed to be protecting.

Today's version of the 'Molossus', the Neapolitan Mastiff, is a stay-at-home guardian for the estate, home and family. From the original ancient dog the Italians have kept the ancients' love of the showy and melodramatic and bred an animal to amaze and astonish. Many say that the Mastiff's fantastic wrinkles and huge head, massive bones and lumbering movement create a dog whose looks alone are enough to deter an intruder.

As Virgil says : "Never, with these dogs on guard, need you fear a midnight thief in your stalls, or the onslaught of wolves."

And there is advice from the poets and philosophers of the time as to what kind of ancient dog makes the best guarding animal.

"It should be large, with a deep bark, and white in colour so as to be more easily recognised in the dark". To protect the dog's neck from the fatal bite of wolves, it should wear a leather collar with nails sticking out - the forerunner of the studded collars of modern times.

And that dog has also survived in modern times: the amazing (we know, because we have one!) Pastore Maremmano Abruzzese, more commonly known as the Maremma.

More about ancient dogs.

|

| Statue of Roman sighthounds, Vatican Museum. |

Ancient Roman animals were not used for entertainment only in the Colosseum. Hunting with hounds was one of the most popular pastimes for the more privileged classes and after the conquest of Britain, wolfhound and lurcher types of dog were imported across the Empire and used for hunting wolves as well as deer.

The writer Arrian describes a breed known as the Vertragus, named for its swiftness - the ancestor of the modern Italian greyhound. Grattius too refers to the Vertragus : "swifter than thought or a winged bird it runs, pressing hard on the beasts it has found" and Pliny recommends the best colour for a hunting dog : "Among all dogs those are the best whose colour is like that of ravenous wild beasts ... or those which have the colour of Demeter's yellow corn, for these are very swift and strong".

The Vertragus revolutionized the hunt, chasing by sight and enabling the hunter to follow on horseback, rather than running behind on foot as had previously been necessary with the larger Laconian hounds which hunted by smell.

Used for coursing as well as hunting, picture evidence suggests that the Vertragus was virtually identical to the modern greyhound. "In appearance" says Arrian, "they are splendid animals with fine eyes, fine bodies, fine coats, and fine appearance. They should be long from head to tail, and the eyes prominent, large and bright, they should astonish the man who sees them."

|

| Today's greyhound : hard to tell the difference. Photo courtesy of the Retired Racing Greyhound Trust UK. |

Compare that with the Kennel Club of Great Britain standard for the modern greyhound : "Strongly built, with long head and neck ... bright, intelligent, eyes, oval and obliquely set ... chest deep and capacious ... coat fine and close."

So our greyhound has its origins in the ancient Roman animals used for hunting, and modern greyhound racing has its origins in coursing. For according to Arrian : "one does not take hounds out in order to catch the beast, but for a race and competition, at least if one is a true sportsman".

Pliny has a different view; he thinks that any form of hunting or coursing "not only does not help the farmer but actually lures him away from his work, and makes him lazy about it". A comment which some may think still applies to greyhound racing today.

Pet dogs in Ancient Rome: cold noses in a warm bed.

But dogs also served another purpose: to keep their owner warm.

When there was no household heat, the dog's body temperature of 101+ degrees was useful for the warmth s/he provided to humans while they were sleeping. Italian winters can be cold.

|

| Modern day 'Canis Melitae' - the Maltese lapdog. |

And they weren't the only ancient Roman animals to play a part in their owner's comfort. Genetic analysis has revealed that lapdogs are among the earliest types of dog to live with people and small dogs such as the Canis Melitae - now bred as the Maltese - were as important a part of the Roman Empire as they are today.

Kept largely by the more privileged classes the role of these dogs in Roman society was exactly as it is today. They had no working function but were to be a docile, friendly companion to those with time on their hands, small enough to be held comfortably in their owner's arms.

Used in ancient Roman daily life as pets, fashion accessories and status symbols for the wealthy and stylish there is also evidence that lapdogs were also used to attract fleas away from their owners.

|

| Mosaic of boy with puppy. |

Roman architecture and art, where dogs are a common feature, tells us that these smaller dogs were also popular as children's pets.

In Pompeii, the body of a boy was discovered with his dog lying over him, trying to protect him perhaps. Mosaics show children playing with puppies, and both children's and adult gravestones regularly show pet dogs sitting or lying by the side of their now dead owner.

And interestingly, even in the time of ancient Rome, as much trouble was taken over both the choice of dogs' names and their accessories as it is today.

Pliny recommends short dogs' names; the poet Ovid recommends suitable names including 'Asbolos' ('Sooty') for a black dog; Dorceus ('Gazelle') for a small, fast dog; 'Tigris' ('Tiger') for a stripey dog; and 'Ferox' ('Ferocious') for a guarding or snappy dog.

As well as having some rather strange views about the treatment of rabies, Pliny had something of an extravagant taste in dog attire. He advises using a collar containing gold which he firmly believes will stop a noisy dog from barking. The forerunner of today's diamante collar, perhaps?

Ancient Roman animals fascinated the Romans.

|

| Bronze lamp with animals. Courtesy of the vRoma project. |

On street corners, coins, dinner plates, mosaics, wall paintings, private houses and arena stages, animals were everywhere in ancient Roman daily life.

|

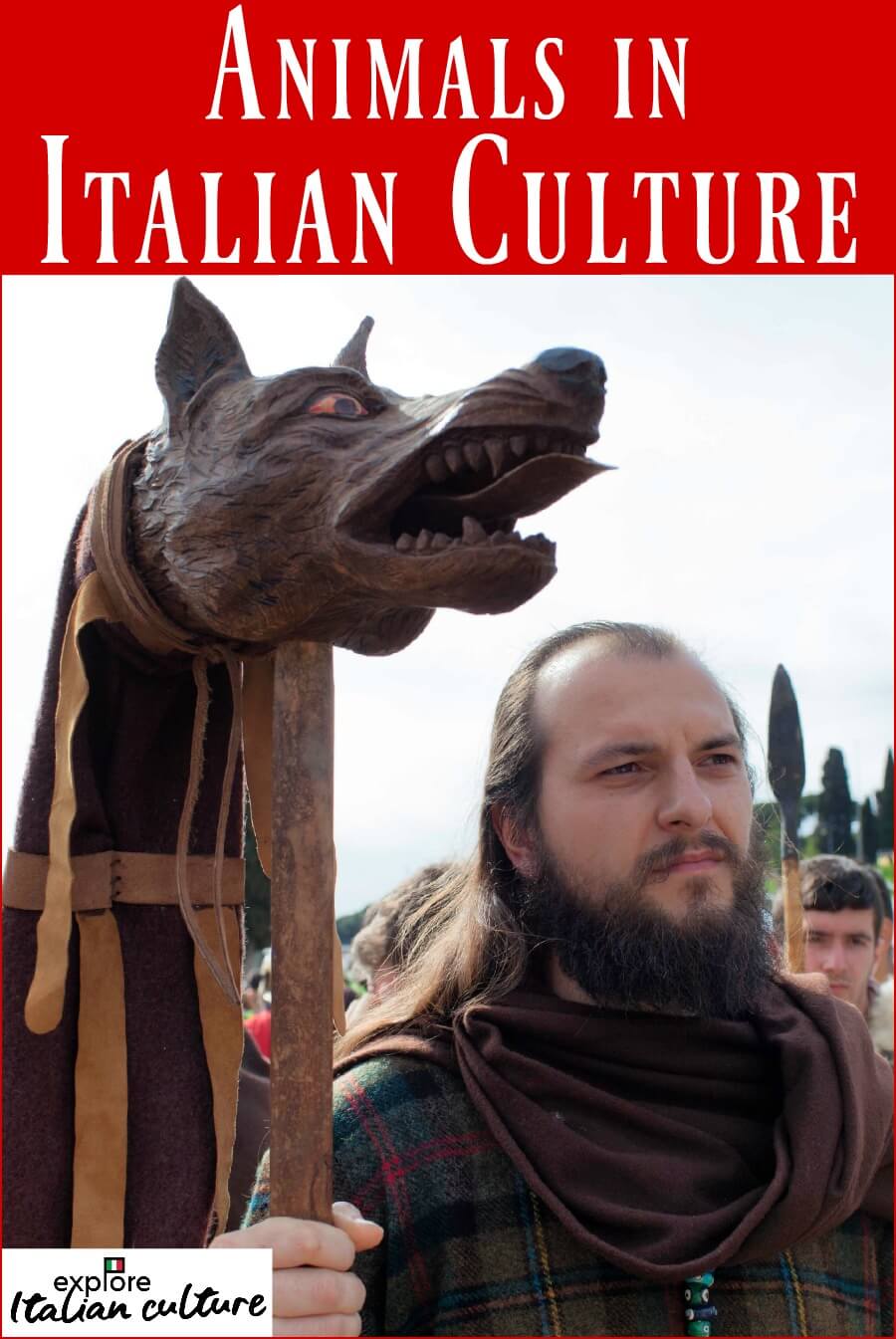

| Romulus & Remus with she-wolf. Image courtesy of vRoma project. |

There is no better image of their importance for ancient Rome than in the story of the city's birth. Romulus and Remus were suckled by a she-wolf, gaining sustenance from the animal to grow and build the foundations of an Empire that would become the centre of the world.

The huge variety of ancient Roman animals as entertainment, working beasts and pets represented the wealth and power of the city as its boundaries grew.

So the history of ancient Roman animals is an important indicator of the Empire's culture and how far Italy has come since those times.

We may view the treatment of some Roman animals as barbaric: pitting bull against bear, elephant against rhinoceros, leopard against criminal - the games devised by the Romans ranged from astonishingly imaginative to brutally cruel and it may be difficult from our point in time to understand the pleasure that huge crowds took from the death or struggle of animals.

Or is it?

... and animals still fascinate in Italy today.

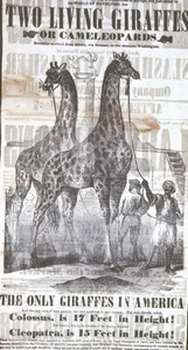

|

| This could be a poster for the Colosseum rather than a circus poster from 1853. |

Were the arena fights staged between different ancient Roman animals so very different from the bull-fighting which still takes place in some European countries as well as South America, or the dog- and cock- fighting and bear-baiting which happen, albeit often illegally, in many countries today?

Parading large numbers of exotic ancient animals in the Roman Colosseum is not so very different from the circus acts which still take place today across Europe. Legislation regulating the use of animals in circuses varies widely across the world, some countries and states banning their performance altogether while others ban only the use of exotic animals.

Within the European Union Austria is the only member to have banned animals from circus acts altogether. Italy still allows, and enjoys, exotic animal performances. The Moira Orfei, for example, a world-renowned Italian circus, advertises acts with elephants, tigers and camels as well as horses and parrots.

As for wealthy individuals keeping exotic pets dressed in human clothes, consider the series of advertisements run for almost fifty years from 1956 in the United Kingdom by PG Tips, a famous English brand of tea, which used chimpanzees in a number of different scenarios.

Is it much different from what the ancient Romans did?

Ancient Roman animals: friend or foe?

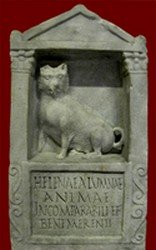

|

| One form of animal death : a beloved pet dog's tombstone. |

Ancient Roman culture was theatrical and exciting - a society without boundaries. Much of the treatment of animals reflected that culture so the history of animals in Italy is a mixed one.

Animals played very different roles during the time of the Roman Empire, but were they treated very differently from animals in Italian culture today?

Animals in the Roman empire were used for entertainment, as working animals and as pets. In a world without television, computers or newspapers, the Romans were fascinated by the beauty and strangeness of exotic animals brought from afar.

They spent hundreds of thousands of denarii capturing, transporting, caring for, housing and training animals from all over the Empire. They queued for hours outside their town's amphitheatres to watch the spectacle and marvel at strangely shaped camels, giraffes and ostriches.

They recognized the strength and importance of animals in war, transport, and agriculture. They kept animals as ornaments, named and pampered them as pets, gave them a full burial, believed in an animal afterlife.

|

| A Colosseum animal hunt. Image courtesy of vRoma. |

And yet at the same time they arranged for the ritual slaughter of the very animals they spent so much time, money and skill in importing and training. They enjoyed animal to animal combat and watched the suffering and agonizing death of the very beasts they so admired.

They sometimes ate the pets they adored. They used animals to make food and ate them as food. They used them as living bedpans to warm their beds and wore them when they were dead as clothes to keep them warm.

And that paradox, those double standards by which ancient Roman animals were treated, is one of the greatest inconsistencies in the whole of the Roman Empire.

Sources and further reading. Where to learn more about ancient Roman animals.

(We recommend these books because we love them, but we should say that if you click these links and buy, we earn a small commission at no cost to you. Read more about affiliate links, here.)

Animals in Roman Life and Art : Professor J. M. C. Toynbee.

There is very little in book form about the role of ancient Roman animals, with the exception of animals in the Colosseum.

However, this book is a passionately written, very detailed explanation of the roles of all sorts of different animals from right across the Empire. It deals with animals as entertainment, sacrifice and pets; looks at the role of wild animals, working animals and domesticated pets; examines the place of animals in the food and clothing chains.

It examines the role of individual animals, from dogs and cats to bears and leopards, and includes birds and even fish.

Detailed enough to satisfy the need of researchers but readable enough for the lay person, this book is an expensive buy but worth it for anyone seriously interested in the subject.

The Colosseum: Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard.

Not strictly speaking about animals, this book contains information about Roman animals only in relation to the Colosseum.

It's a hugely entertaining book full of interesting facts about the Colosseum rather than the usual rather dry information.

Written by two leading historians, it is humorous and based on contemporary writings and images. From its original purpose to its strange after-life, the authors trace the history of the building in a lively, engaging, readable format.

Highly recommended.