Ancient Roman Daily Life: how it impacts on Italian culture now

Ancient Roman daily life.

Ever wondered where the doggy-bag originated? Or why there's so much graffiti in modern day Italy?

The answers lie in Ancient Roman culture!

In this article, we'll look at:

- where the Italian obsession with food originated, and why ancient Romans were the first to use doggy-bags

- why graffiti is not a modern day phenomenon

- how Roman clothes were the start of the Italian fashion icons

- why chariot racing has more to do with modern sporting culture than you might think, and

- why ancient and modern rulers are not so different!

#1: Ancient Roman daily life included celebrity chefs, beefburgers, and doggy-bags

In the early days of the Republic, ancient Roman daily life was fairly austere and food was simple, with little meat. But as the Roman Empire grew in importance, food assumed a far more prominent role. Mosaics representing available foods adorned the houses of the rich and powerful, and recipes which have survived to the present day detail sumptuous meals, even for those on a limited income.

Dining became an elaborate affair. Expensive food, and a lot of it, was an obvious way of displaying status and wealth to friends and business partners.

A celebrity chef of his time, Marcus Gauius Apicius, wrote a renowned recipe book entitled "De Re Coquinaria." In it he gives a recipe which mixes minced meat with bread soaked in white wine, stone-ground pine kernels, green peppercorns and salt. The mixture was formed into small balls and cooked over a fire.

Barbecued beefburgers, ancient Roman style!

As for the doggy-bag, dinner guests knew that the foods on offer would be both extravagant and plentiful. It was an accepted part of daily life that when invited out, guests would take with them their own personal over-sized napkin.

As well as being used to wipe hands and mouths, guests would be encouraged by the host to use it to take home leftovers of the dishes they had enjoyed as a sign that his meal had been well received.

So although it's one of those things you would never guess, ancient Roman influences on Italian culture today stretch as far as foods.

#2: Ancient Roman Daily Life: why graffiti was so important in ancient Rome

So you've visited Rome and thought the graffiti found all over the city is the work of modern vandals? You couldn't be more wrong.

Originating from the Italian word 'graffiato' ('scratched'), the beginnings of 'modern' written scratchings which use words to express curses, slogans, love or hate are to be found in the graffiti of daily life in ancient Rome. Graffiti has been discovered not only in ancient Rome but in all parts of the Empire, from Egypt to Greece and beyond.

The ancient romans even invented the fountain pen!

Ancient graffiti artists, as well as being well-travelled and prolific, did seem to have some respect for ancient Roman architecture and art. They generally avoided defacing wall paintings and mosaics and most graffiti is found on columns and walls.

Sometimes comic, often lewd, frequently giving information about times and locations of events - an ancient version of fly-posting - graffiti has become a rich source of information for historians about ancient Roman daily life, an indicator of how ordinary people thought and felt. It tells us things like:

Political satire - Roman graffito by Peregrinus, perhaps the first satirical cartoonist

Political satire - Roman graffito by Peregrinus, perhaps the first satirical cartoonist- Who loves whom: "Helena amatur a Rufo" (Rufus loves Helen);

- ... and who hates whom: "Cosmus Equitiaes magnus cinaedus est suris apertis." (Equitas' slave Cosmus is a big pervert with his legs wide open);

- Which gladiators were popular and why: "Suspirium puellarum Celadus thraex" (Celadus the Thracian makes the girls sigh)

- ... and who had won the most recent fights: "Albanus scaeva liber victoriarum XIX vicit" (Albanus, left-hander, of free status, victorious)

- Who stood for election and what the popular view of them was: (see graffiti of Emperor by Peregrinus, above);

- Who has been breaking the law: "ladicula fur est" (Ladicula is a thief)

- Where to find a prostitute: "Nuceria quaeres ad porta romana in vico venerio novelliam primigeniam" (At Nuceria, look for Novellia Primigenia near the Roman gate in the prostitute’s district);

- ... and even comments on the learned men of the day; in the ruins of a Roman school was found the inscription: "Socrates taedium est" (Socrates is boring).

Graffiti depicting Viking ship, from ruins of Pompeii

Graffiti depicting Viking ship, from ruins of PompeiiGraffiti was written by people at all levels of society, and most of it is surprisingly literate. Being able to see the words and gauge the feelings of commoners who would otherwise be forgotten is one of the appeals of ancient graffiti.

They are exceptional evidence of Roman life, distant echoes for us of public deeds and private passions. The general content of the writings may not be very different from those found on inner city walls today, but searchers after ancient Roman facts can use it to plot the moods of local communities and to examine how they have influenced Italian culture, traditions and history.

So next time you visit Rome and you're tempted to complain about the graffiti you'll see throughout the city, stop and think: in two thousand years' time that graffiti might be used by historians of the future as a window back onto our own civilization.

A story of a people who by then will have long passed into the history books.

#3: Ancient Roman Daily Life: why purple was the 'in' colour for fashionable clothes

Clothes were as important a part of ancient Roman daily life as they are for Italians today. Ancient Roman clothing was a symbol of status and power and no other colour more clearly represented prestige than purple. Only the most expensive dyes were used to produce purple and so it became synonymous with wealth and power.

Plain white toga virilis

Plain white toga virilisThe toga might have been the height of ancient fashion, but it was probably not terribly comfortable and was largely used for ceremonial and social occasions.

Too cumbersome to be worn by workers or soldiers, by the 2nd Century B.C. only Roman citizens could wear the toga and whilst not used a great deal in the mundane activities of daily life in ancient Rome, it certainly became an indication of social standing.

Typically of ancient Roman clothes, the more distinguished the wearer, the more extravagantly the clothing was distinctively marked. The toga of the lowest class citizen, 'toga virilis', was a simple white garment and not marked at all.

The next step up was a bleached toga or 'candida' worn by those standing for office - hence the word 'candidate' - but, apart from togas used in mourning which were of a plain dark colour, it was not until public office was attained that togas became adorned.

Ancient Roman fashion: left to right: the distinctive dress of Magistrate, early Emperor and General

Ancient Roman fashion: left to right: the distinctive dress of Magistrate, early Emperor and GeneralThe 'toga praetexta' was where colour began: white with a broad purple stripe, it was worn by senior magistrates, consuls, senators, those priests engaged in sacred rites, and soothsayers.

Fashion in ancient Rome dictated that it should be accompanied by similarly coloured shoes.

The height of ancient Roman fashion as far as mortals were concerned was the 'toga picta' of purple, embroidered and intricately decorated in gold. Worn by triumphant generals and the early Emperors it was adapted from the precisely named 'toga purpura', an all-purple toga worn by the early kings.

But the toga of togas in ancient Roman daily life was the 'toga trabea'.

A garment of pure purple, it was initially available to gods only. Later, in his attempt to appear more 'god-like' to the masses, Julius Caesar adopted it as part of his regular dress. Subsequent emperors followed suit by using this toga during state occasions.

To this day, purple is associated with royalty and nobility.

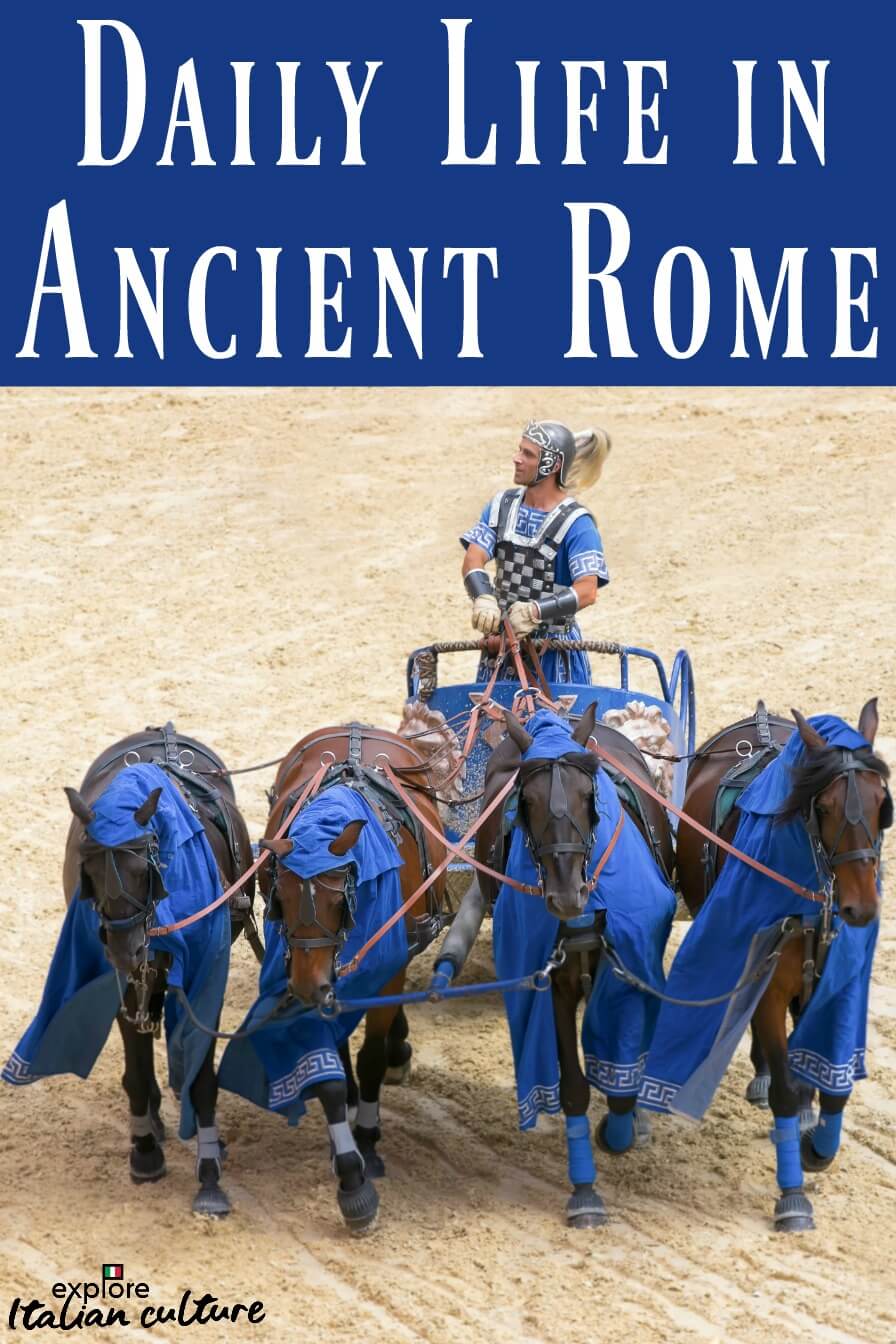

#4: The Circus Maximus held more spectators than the biggest sports stadium in the world today

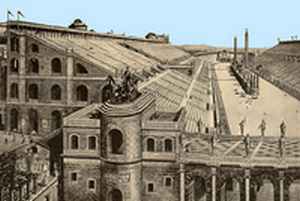

Reconstruction of Circus Maximus, courtesy of Barbara McManus, VRoma

Reconstruction of Circus Maximus, courtesy of Barbara McManus, VRomaThe architects of the Roman Empire were not known for doing things on a small scale. When they built the Circus Maximus, the ancient Roman hippodrome and chariot-racing venue, they meant business.

They built it to hold an audience of between two hundred and fifty and two hundred and seventy-five thousand spectators. Even the ancient Roman Colosseum, one of the great symbols of Imperial Rome, could only hold around sixty thousand.

We are able to extract from the writings of individuals such as Dionysius of Helicarnassus who lived in ancient Rome, information which enables us to reconstruct how the Circus Maximus would have looked.

The arena was two thousand feet long and seven hundred feet wide. The porticoes held seats three tiers high on three sides, the fourth side left free for the horses' starting boxes.

Outside the arena were further porticoes which held apartments and shops. Seats were not numbered; the only way to secure the best was to arrive early.

The modern equivalent - but this Tokyo racecourse

is smaller.

Photo courtesy of world stadiums.com

The modern equivalent - but this Tokyo racecourse

is smaller.

Photo courtesy of world stadiums.comCan we, with all our modern building equipment, compete with the grandeur of ancient Roman daily life, their inventions and feats of engineering?

We can come close but not quite match it. The Indianapolis speedway track, the largest arena in the world today, holds a maximum of two hundred and fifty thousand. The largest racecourse in the world is in Tokyo and holds two hundred and twenty three thousand.

As for football stadia - they come nowhere near.

The largest sports arena, the Rungrado May Day Stadium in North Korea, holds a mere one hundred and fifty thousand. The largest American Football stadium - the Beaver Stadium at Pennsylvania State University - holds one hundred and seven thousand.

The most famous British soccer stadium, the 'new' Wembley, holds ninety thousand. And despite all the Italian culture traditions of soccer the largest football ground in Italy, Roma and Lazio's Stadio Olimpico, holds just seventy-three thousand.

#5: The dangers of daily life for Ancient Roman rulers

We know from the writings of ancient Roman daily life that after their death, ancient Roman Emperors were often deified.

We also know from writings at the time that some Emperors considered themselves to be living gods - Julius Caesar's family, for example, claimed to be direct descendants of the goddess Venus.

Nero the tyrant : original bronze cast at British Museum.

Photo by Cath

Nero the tyrant : original bronze cast at British Museum.

Photo by CathBut it has to be said that the gods did not always smile on ancient Roman Emperors. They may have been popular once dead, but whilst still alive they were not always given such a good deal either by the people they governed or by their own army and followers.

In the period 27 B.C. to the fall of Rome in 476 A.D. there were a total of one hundred and twelve ancient Roman Emperors (Source : 'Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families', ed. Richard D. Weigel, Western Kentucky University). Of those, only fifty-five died from illness, natural causes or in battle.

Of the remainder, twelve were deposed and mutilated; the remainder were either murdered, often by the very people who had brought them to power, or took their own lives before their army could do it for them.

The unluckiest year for Emperors was 236 A.D. when there was a total of six Emperors. One was killed in battle, four were murdered and there was one - no doubt very nervous - surviving Emperor at the end of the year.

The Emperor's own elite troops, the Praetorian Guard, were ironically often those who did the deed.

Consuls and army officials seemed a little unsure of the best age for a man to accede to the position of Emperor. They varied from the elderly - Gordian I, at the age of seventy-nine - to children - Gratian was eight years old when he came to the throne.

It's noticeable that those who appeared to have reputations as the cruelest of the Emperors were those who came to the position as youngsters.

Probably the best known example is Nero, Emperor of Rome between 54 and 68 A.D.. He was aged just sixteen when he rose to this position of unrivalled power. Although his reign began well he later became unfettered in his cruelty and his sacking of Rome, attempted destruction of Christians, and pushing of his own Senators to suicide were all planned with the utmost precision and cruelty. His executions were so grisly that even the commoners, not known for their compassion, displayed sympathy for the victims.

Ancient Roman daily life might have been hard, but Nero eventually went a step too far. Faced with a successful uprising, he was finally abandoned by his supporters and committed suicide.

Caracalla.

Photo taken at the British Museum by Cath

Caracalla.

Photo taken at the British Museum by CathBut perhaps the unluckiest Emperor of all was Caracalla. He had a reasonably long reign and brought about some noteworthy changes in ancient Roman daily life, the three most significant being increases in pay and legal rights for soldiers, the bestowal of Roman citizenship upon all free residents of the Empire, and construction of the magnificent baths in Rome that would bear his name.

It was his religious devotion that led to Caracalla's murder in 217.

On a trip to the temple of the moon-god at Carrhae he allowed himself to be accompanied by only a small, select corps of bodyguards. During the journey back he was ambushed while defecating at the roadside, the alleged assassin one of his own Praetorian Guard.

Not so very different from politicians of today, whose main aim often also seems to be to stab each other in the back - metaphorically speaking, of course!

Want to know more about Ancient Rome and its impact on modern day Italy? Try these links!

All images on this page, unless otherwise specified, are courtesy of the VRoma.com project.